Lamming Mouse circa 1974

I had grown up creating programs on punched cards, or paper tape. It was very exciting when I got to use a time-sharing system. The ‘new’ way to interact was using a teletype. A teletype could output 10 characters/second onto a paper scroll. This was not that unreasonable given the time it took for the computer to respond to a command. Some days, you could type a line and wait many minutes, perhaps 20, for a response. One of the cultural side-effects of this was that we lowly beings used to go use the computer at night. Computers always ran faster at night in those days.

I had grown up creating programs on punched cards, or paper tape. It was very exciting when I got to use a time-sharing system. The ‘new’ way to interact was using a teletype. A teletype could output 10 characters/second onto a paper scroll. This was not that unreasonable given the time it took for the computer to respond to a command. Some days, you could type a line and wait many minutes, perhaps 20, for a response. One of the cultural side-effects of this was that we lowly beings used to go use the computer at night. Computers always ran faster at night in those days.After I graduated, I stayed on to do some research, and joined George Coulouris’ research team who lived in a converted college theater called Stern Hall. We had one computer, an Interdata Model 4. It did not run faster at night because it was a single-user machine. Tony Walsby has written amusingly about this period. However, nothing much changed for me. Students were low in the pecking order and could only get useful slots of time at night.

|

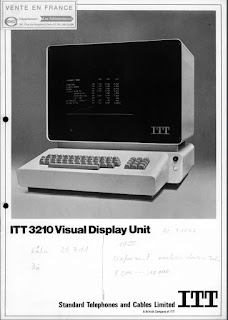

| ITT 3210 |

Sometime around 1972 we got our own time-sharing system which ran Unix on a PDP 11/40. This was a fantastic improvement in some ways, and worse in others, and marked the time I got my first email account. Our time-sharing system still had an unpredictable response time, but you could “get time” on them more easily.

What was especially wonderful was that we didn’t have to use clunky teletypes. We had about 6/8 “glass teletypes” aka “dumb terminals”. Each of these ITT 3210s was connected by 9600baud wires to UNIX. The screen displayed an 80×24 (?) grid of fixed font characters with a few different faces. Theoretically the dumb terminal was almost 100 times faster than a teletype. But we still used them in a very simple way as a “glass teletype”.

One day I was talking to an engineer who had come to fix a broken 3210. It was late in the day, and we got chatting, and he told me something that caught my attention. Apparently it was possible to send special ‘escape’ characters to the terminal that would allow you to write a character anywhere on the screen. This was well known in the UNIX world, but not so well in Stern Hall. We didn’t yet have the special driver upgrades to use them in a cleverer way, but I think Richard Bornat, or Jon Rowson eventually took care of that.

So I got to thinking what life would be like if you could write stuff anywhere. Having been told that the airline booking systems had created a form-filling kind of UI, I got to playing around to see if I could divide the screen into several smaller screens. I have to confess that I was thinking that I could have multiple streams on interaction running at the same time, instead of the usual one – which meant I could probably hog more of the machine time. I started by partitioning the screen, but soon found that I could simulate overlapping terminals.

|

| Text Terminal (hand on mouse) |

I recall that I actually managed to hack a system with 2/3 overlapping terminal areas, which looked terrible, but kind of worked. I showed to Jon Rowson. Jon, who was really smart, got fired up and spent a year or so building a complete window system using the same principle. It was used for a whole bunch of projects. Switching the input focus between windows was clunky. You either had to tediously move the cursor to the target window using cursor keys, or had to cycle through all the windows using a special ‘next-window’ key. Most systems just used a couple of windows.

At about this time, Mike Cole started a project to build a terminal that would do this overlapping windows thing properly. He and Tony Walsby built the Text Terminal. It seemed very cool, and I wanted to redo my multi-window thing on it.

Moving between windows was still a pain, and Tony had implemented a joystick to make it easier. I had fiddled with a trackerball idea, which I thought was better because you could scoot it fast to move fast. I actually started work on a tracker ball, but it soon became clear that it was a lot easier to use if you turned it upside down and rolled it across the desk to re-position the cursor. Of course the cursor had to move in the opposite direction, but it seemed to work well.

So I decided to build an upside-down tracker ball, using wheels and some home-made shaft encoders. The wheels were turned up on a lathe from brass rod. The shaft-encoder (a rather superior description for what it was), was a Mechano pulley wheel – filed down to be small enough, through which the light from an interrupter could shine. The whole lot was stuffed in an off-the-shelf plastic box, had a few buttons added, and was used to actuate the appropriate cursor keys on the Text Terminal (I think Tony did that bit). Against all expectations, it worked amazingly well, but was very heavy. You could get insured if you dropped it on your foot. Someone later made a furry cover for it with eyes, ears and whiskers.

The other day I was cleaning out my boxes of junk and I came across the gubbins. It made me laugh to see it again, and see the very variable standard of workmanship.